If you ask average enthusiasts about the golden age of supercars, you will get different answers. Some might tell you that the late ’60s were the definitive era, with the glorious Lamborghini Miura setting the segment’s standards. Others might suggest that modern times are the pinnacle of the supercar class with incredibly fast and advanced Porsche 918 or Ferrari LaFerrari. However, neither are right. The golden age of supercars was the mid-90s. This was when the analog approach and hand-built techniques met the modern technology, resulting in incredible cars, legendary racing victories, and features never before (or since) seen on production road-going vehicles. What car can best describe this short but memorable era? The unrepeatable McLaren F1, of course.

The story about McLaren F1 must be started with a basic explanation of what the F1 is. Yes, it is a supercar, but it is far more than just an extremely fast and capable vehicle. The McLaren F1 is the materialization of the idea of speed and reaching the limits of what was possible at the time. It is the “no-cost” car whose only purpose is to be the ultimate driving machine (pun intended) and the superlative vehicle in just about any sense of the word. The F1 was like Haley’s Comet, the car so special and unique that it only appeared once in a lifetime with no predecessor and no successor planned. The way it was engineered and manufactured is still impressive and unique in the car world. We will now explain it in greater detail.

The McLaren F1 was the brainchild of Gordon Murray, a famous British race car engineer and one of the people behind legendary McLarens’ success with Honda in Formula One in the late 80s. The iconic times which market many wins of McLaren cars with Ayton Senna behind the wheel. Murray felt that all that racing experience and know-how should be transformed into one great road car, which would be the pinnacle of automotive engineering. In fact, Murray also wanted to install the version of Honda’s Formula One engine in the car, but the Japanese company declined.

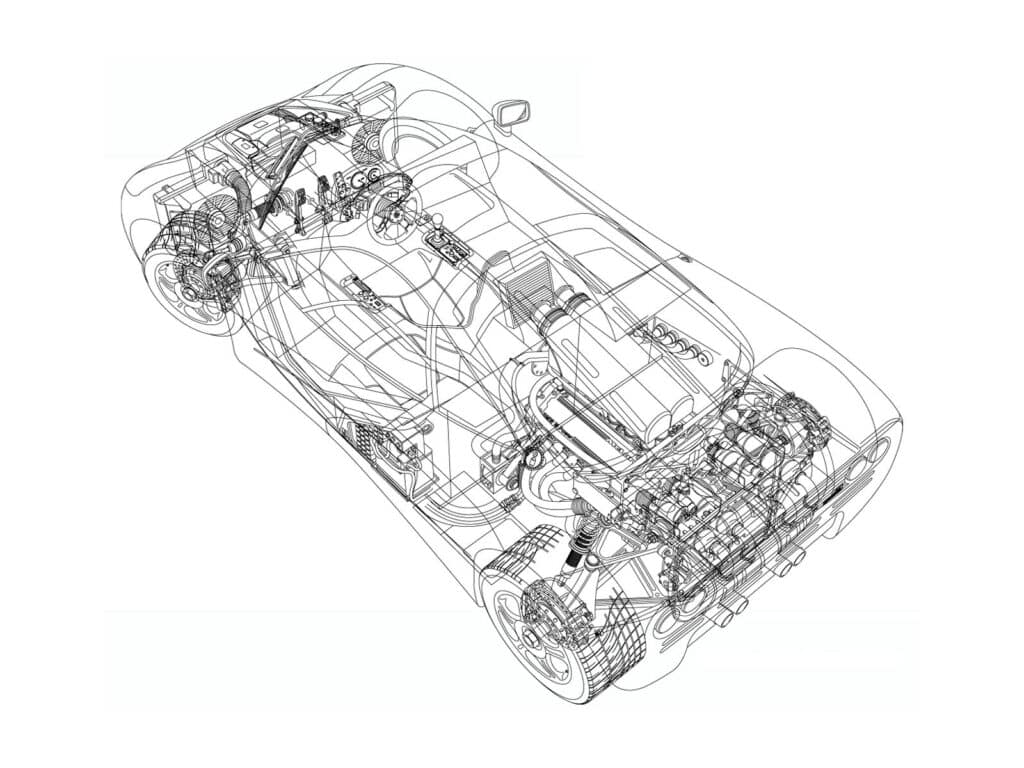

In order to build such a car, Murrey wanted a bespoke construction and use of the lightest and strongest materials. Using his Formula One experience, he decided that carbon fiber would be the best choice for the chassis and body, making the F1 the first production vehicle with carbon fiber monocoque chassis. Aside from carbon fiber, McLaren used magnesium and aluminum to construct the chassis and suspension components and develop its own alloys, which were lighter but stiffer than what was commercially available at the time.

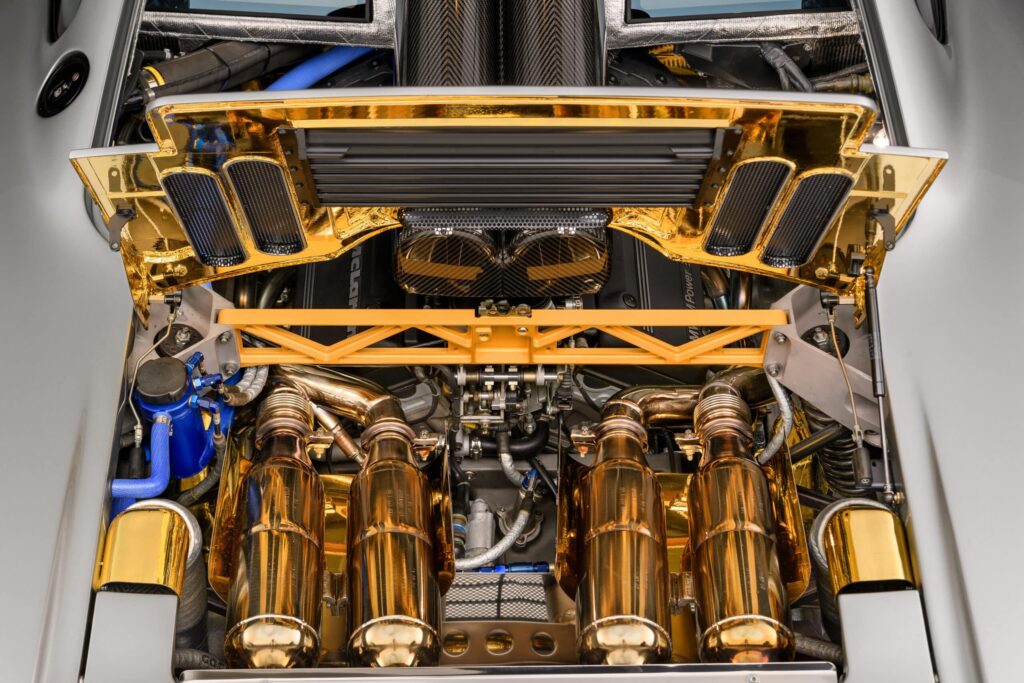

The next piece of the puzzle was the engine, and after failed negotiations with Honda, Murray turned to BMW. Working closely with legendary BMW engineer Paul Roche, McLaren managed to source a 6.1-liter S70/2 V12 engine, a special and improved variant of the famous BMW’s V12 unit. The engine was all-alloy with variable valve timing (a novelty in the early ’90s) and race-style dry-sump lubrication. The S70/2 was, of course, hand-built by the M Performance division and featured numerous unique mechanical contraptions like two injectors per cylinder and a separate ignition coil for each cylinder, among other things. The result was 618 hp and 479 lb-ft (650 Nm) of torque which for the early ’90s were astonishing figures. However, the coolest detail about the engine was the fact that the engine bay was covered in gold foil! The gold wasn’t luxury detail for catching the attention of wealthy car buyers but a necessity due to its heat isolation capacity. This way, Murray managed to keep extensive heat produced by the engine away from fuel cells and the cabin.

The final part was the design, and for that, McLaren contracted another British automotive legend – Peter Stevens. Stevens already had impressive experience designing extreme race and road cars, and before drawing the F1, it created another British supercar legend of the 90s, the Jaguar XJR-15. However, even though he was given the full freedom to create the shape he wanted, one exciting feature must be included – an unusual, three-seat layout. Gordon Murray was fascinated by this concept and insisted that this be included in F1, so Stevens created an everlasting look with characteristic supercar features like low silhouette, aerodynamic shape, butterfly doors, and central driving position with a passenger seat on each side. Because the McLaren F1 was envisioned as a road car, not an all-out racer, the interior was relatively comfortable with working A/C and rear defroster; the car even was delivered with an audio system and titanium tool kit, which suggested that Murrey intended for F1 to be driven regularly by its owners.

As expected, the first magazine reviews and tests clearly stated that F1 is the next level in automotive engineering and design. Although incredibly fast and capable, it wasn’t too harsh to drive and could be used in everyday traffic, even though most owners decided not to. With reasonable comfort and good driving position, it was decently comfortable on long drives, and the suspension managed to cope with the bumps on the road. The clutch pedal wasn’t too heavy, and the steering was light even though it wasn’t power-assisted. There were no stability control or electronic aids. Still, with a composed chassis and low weight (1,150 kg – 2,500 pounds), it was very controllable and docile at moderate driving but planted and stable at triple-digit speeds.

The official presentation took place in 1992 in Monaco, and immediately, the F1 was the talk of the global car community. The vast number of innovative solutions, features, and engineering concepts fascinated enthusiasts, along with the performance. Even today, F1 can match modern supercars with 0 to 60 mph time of 3.2 seconds and a top speed of 240 mph, making it the fastest car in the world at the moment. Of course, such an advanced machine came with a hefty price tag, and the brand new McLaren F1 cost over $800,000, which was much more than the rest of the competitors, if there were any. Some reports from the period state that brand new McLarens were changing hands for around $1 million. In the mid-90s, the list of original F1 owners included some of the most important names in the world’s entertainment industry and politics. Guys like Elon Musk (way before its Tesla adventure), Jay Leno, George Harrison, Rowan Atkinson, and Sultan of Brunei all were proud owners, as well as fashion magnate Ralph Lauren and Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason. Most of them paid around $1 million for the privilege, and today, well-preserved F1s sell for 20 times as much! Production lasted six years, from 1992 to 1998, during which time only 106 cars were completed; most were road-going models, but 28 vehicles were in GTR, racing specification.

Even though the McLaren F1 was primarily a road car, it was built by people with deep roots in motorsports, so it was only natural that F1 tried its hand at racing. The racing spec model, the GTR, was introduced in 1995 and featured necessary modifications and improvements. The most significant one was the “long tail” design which improved aerodynamics at high speeds and added a big spoiler. The McLaren F1 GTR raced in the newly formed GT1 FIA racing series along with Porsche Carrera GT and later with Mercedes CLK GTR. As expected, McLaren F1 GTR proved to be a fantastic race car entering numerous GT-style racing series worldwide and winning as many as 38 races globally. However, its most significant achievement was the win in 1995 24 Hours of Le Mans. After a dramatic race, McLaren F1s managed to finish 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 13th and declare its domination in the world of sports cars. In honor of such an iconic achievement, McLaren released a limited run of 5 cars called F1 LM, which were slightly different from the standard models and featured race-spec equipment and an improved aerodynamics package.